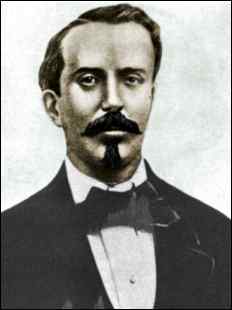

On this day, in 1868, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes issued his proclamation of Cuban independence from Spanish rule: El Grito de Yara. Thus began "Cuba's first formal war against Spain" which also brought to prominence Cuban heroes like Antonio Maceo, Maximo Gomez and, of course, Jose Marti.

On this day, in 1868, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes issued his proclamation of Cuban independence from Spanish rule: El Grito de Yara. Thus began "Cuba's first formal war against Spain" which also brought to prominence Cuban heroes like Antonio Maceo, Maximo Gomez and, of course, Jose Marti.These names were called out earlier this month (October 1st) when the "Miami Declaration" was announced at the Manuel Artime Theater, in front of more than 800 Cuban exiles in Little Havana. By memorializing these men, who fought an armed struggle against Spanish imperialism and brutality, some in the Cuban exile community have embraced the soldier mentality, the code of honor, the act of war.

Orlando Bosch was there that night and received a round of applause. US Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen was also there and surely clapped at the man whom she supported in 1988 as "a valiant freedom fighter."* But, Bosch represents the perverted example of what Maceo, Gomez and Marti fought for. In a 2006 interview, Bosch called the explosion of a plane including women and children "a wartime target" and that "a bomb is proof of rebelliousness, proof of bravery."

Eduardo Arocena, and Santiago Alvarez were other names called out that night. Arocena was sentenced in 1984 to life in prison on several criminal charges and his involvement as the "chief bomb maker" in an attempt to prove his "bravery." Alvarez was another who proved his "rebelliousness" by keeping a "staggering amount of illegal weaponry and ammunition" in one of his apartment complexes, which was soon discovered by federal agents. His original 20-year, 6-count indictment was soon reduced significantly after he surrendered more illegal weaponry, which "consisted of dozens of machine guns, rifles, C-4 explosive, dynamite, detonators, a grenade launcher and ammunition." Alvarez is scheduled to be released from prison before the end of this year.

The official announcer of the "Miami Declaration", Armando Perez-Roura, has publicly stated that an armed struggle is justified, even asking presidential candidate, John McCain, last March if he would support such measures against Cuba.

But, today is not 1868. We don't live in an era of such brutality and violence. Since the end of the second World War, our integrated and interdependent society is structured under laws that prevent such chaos to spread. Back in 1868, laws that protected international human rights didn't exist; we didn't have international criminal tribunals; we didn't have universal protection under the law.

Today, we depend on such values. We care about what is happening across the globe in Burma, we are concerned about the talks between North and South Korea, the peace process in Nepal, or the criminal trial of Alberto Fujimori. We care because their effects will have profound influence in our global society.

But, if we support violence now, in a world far removed from the time of Maceo, Gomez or Marti, the consequences can be far too great to bear, and the risks too great for a society that does not support it. This time, the brave ones will call out "peace", and an end to war.

* [The Miami Herald, February 23, 1988, "Politicians Plead for Bosch's Release" by Carlos Harrison.]

No comments:

Post a Comment